[google doc version for commenting]

Introduction

This post describes one version of a problem-solving technique I call “Red Penning”, specifically designed for solving a problem when it feels like no solution exists, under the assumption that working memory limitations are a bottleneck to finding more complex or less familiar solutions. It is makes use of external working memory aids to cycle through focussed sessions of

- describing a problem

- resonating with the description

- making the description more pessimistic

- critiquing that pessimism

- brainstorming solutions

These five steps happen pretty quickly it my head numerous times per day, most times over over a course of 5-10 seconds. It usually also happens a few more times per day over a period of minutes or hours.

Related blog posts

These are not required reading, but might provide some context.

-

Red-penning: rolling out an experimental rationality / creativity technique (early thoughts on red-penning)

Tools needed

To use this technique, you will need

- Several multi-color writing spaces, e.g. Google docs using different font colors, loose leaf papers with multiple pen colors.

- A drawing space simultaneously visible alongside the writing spaces, e.g. another piece of paper, or an iPad with an Apple Pencil. Simultaneous visibility is important for me, so I can switch between the spaces just by moving my eyes instead of having to use my hands to switch between computer windows.

Prerequisites

You can skip this section on first reading. If the technique seems hard or isn’t working, come back and read this section to make sure you’re not missing a key dependencies.

- Resonating. The ability to check if some written words “resonate” with you intuitively, separately from whether they seem logically correct. For example, the “resonating” step in Gendlin’s Focusing technique can be used here.

- Critiquing. The ability to notice holes in a logical argument; basically, the thing that makes you say “Well, not necessarily…” when someone makes too strong of a claim. I don’t know a good reference for this, aside from a high school or college class on writing proofs or arguments, or just having it as a personality trait.

- Dedication. The ability to sit with a problem for a total of 30-60 minutes, allowing for breaks to get food, water, or other forms of physical comfort, but not intentionally taking breaks for “mental comfort”… things like reading Facebook or playing video games. It’s okay if your thoughts wander, as long as you keep bringing them back to the things you are writing. I hear Deep Work is a good book for learning to do this, though I haven’t read it.

- Actually trying things. Once you have a solution, you’ll need to actually try it. For example, CFAR’s Trigger-Action Plans are good for this.

The technique

Pick a problem. If you don’t know what the problem is, wait until a time when you feel stressed about something and use that. If you don’t know what the problem is, write down a meta-problem like “Something seems wrong or hard right now and I don’t know what it is.”

- Describe. Using a fresh writing space, describe the problem in the form of written argument about its causal structure. During this step, don’t be too critical; just write what seems natural.

Example:

Writing Space #1: Describing & Resonating

|

- Resonate. Read over the argument from (1) to see if the written words resonate instinctively/intuitive with you. If any phrasings do not resonate, use the eraser to change the phrasings until they do.

(If you don’t like erasers, just keep re-writing on a new sheet of paper each time and tossing out the old versions. Your goal is both to produce a version of the description that resonates, and to remove non-resonant versions of the description from view.)

For example, suppose “anxious” felt more apt than “stressed”, and suppose it felt maybe it After making edits, the description could look more like this:

Writing Space #1: Describing & Resonating

|

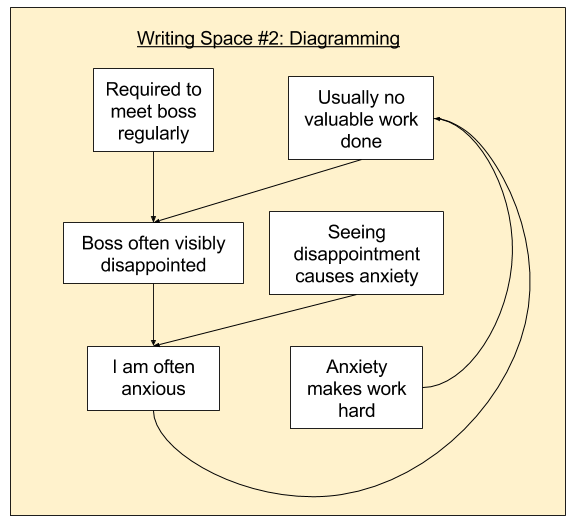

- Diagram. In a new writing space that can be visible at the same time as the Describing & Resonating space (e.g. paper, or an iPad with an Apple Pencil), draw a diagram depicting the causal structure of the problem. Feel free to adjust the argument in the Describing & Resonating space if you experience shifts in your thinking as a result of the diagram**.

- Pessimize. Open a new writing space that can be visible at same time as the diagram. Using the diagram as a guide, try to write a strong argument that your problem is impossible to solve.

If the writing out this argument feels bad or wrong in a way that makes it painful to agree with, that’s great! It means you’re sort of skipping ahead to the next step, which is fine and good.

Writing Space #3: Pessimizing & Critiquing

|

- Critique. Reflect on what seems most weak or wrong about the pessimism argument, and use a different writing tool (e.g. a red pen, google doc comment, or different font) to add comments or highlight the objections you have.

The result could look something like this:

Writing Space #3: Pessimizing & Critiquing

|

- Brainstorm solutions. Read over the critique you just produced and reflect on which, if any, of your comments lend themselves to solutions you could try. Make sure each criticism in Space #3 is reflected in your brainstorm in Space #4. Spend a little time looking at each solution idea to see if you can make a more effective version of it.

Writing Space #4: Brainstorm solutions

|

- Try your favorite solution(s). Ideally, try your most promising solution(s) immediately. Otherwise, decide on a concrete place and time to start trying each solution you feel excited about, e.g. using trigger-action plan that includes a date or time to revisit whether the plan worked.

- Revisit and reflect. Return to your notes at your planned time, or if your attempt feel like the attempt failed, whichever comes first. Amend your notes to reflect why it failed or succeeded, and maybe repeat this procedure in light of your new experience.